“Social Distinctions in Language”

Introduction

We live in a world of over 6.5 billion people who converse every day. What we take for granted is the language that we use to speak with is built not by our own mental lexicon, but by the very words we pick up from our social environment. Many people confuse sociolinguistics and the sociology of language. In “An Intro to Sociolinguistics”, Ronald Wardhaugh differentiates these two areas of study. He says that Sociology of language is how language affects society whereas the area of sociolinguistics seeks to determine just how society affects language development (p. 12). This paper focuses on the latter. However, sociolinguistics is far too vast to cover in any one paper because language has a plethora of different social influences. Therefore this paper seeks only to describe four main areas of differentiation: (1) Differences according to social class, (2) Differences according to age variation, (3) Differences according to geography, and (4) Differences according to gender.

Differences according to social class

Every society is made up of social classes, and these social classes are more commonly economic classes as well. Therefore, it is important to note that money has an influence on language just as it does on almost every other aspect of life. That being said, this paper only seeks to differentiate language between the social classes, not define its development from an economic standpoint. Differences between social groups are referred to as “sociolects”. It is also important to note that those in a particular class may speak differently from others within that same class, because they are aspiring to be in the higher class. This is referred to as “class aspiration”.

The distinctions in language between the different social classes are referred to as “social language codes”. This idea was created by Basil Bernstein, a well-known British sociolinguist. In his paper, “Elaborated and Restricted Codes: Their Social Origins and Some Consequences” he referred to the proletarian (lower/working classes) language usage as “restricted code” (p. 57). He states that this type of code focuses on unity, because it allows for stronger bonds between fellow working class citizens. It is characterized by people behaving in a way that creates distinction between different roles such as gender and age roles. People using the “restricted code” do not have to be as precise in meaning because the meaning is generally shared by all other working class members. As stated earlier it focuses on unity because it relies on shared knowledge and shared experiences rather than explicitly saying what one means to say.

Bernstein refers to the bourgeoisie (middle/upper/ruling class) language usage as “elaborated code” (p. 57). This code is a language that is focused on economic and educational advancement. It is focused not on the group as a whole, but on the individual. This group more often than not uses what is referred to as “standard” language. In America this is referred to as SAE (Standard American English). While the lower class distinguishes between gender, age, and other roles, the middle/upper class is almost opposite. Members in the upper/lower classes tend to negotiate to achieve specific roles, rather than assign them to individuals based on their distinctions. This leads to a lack of unity, due to the lack of shared experience, focusing on the individual’s inclinations, rather than the sharing of meaning.

Differences between social groups have led to tensions because of the different language codes that they use. In some areas it is often dangerous to use an “elaborated code”, because of the negative connotations that come from using a “prestige dialect”. Members of the lower class will see it as a prideful or arrogant distinction. This can also be said of the middle/upper class where a person who uses “restricted code” will be looked down on as uneducated. As well as this some social groups will use an “elaborated code” when doing certain tasks, such as going to school or work, and will use “restricted code” when they are doing other tasks, such as hanging out with friends. This is referred to as “covert prestige”. This represents the current trend in American language usage. Now that we’ve looked at distinctions between social groups we will take a look at differences between age groups.

Differences according to age variation

There are many topics that come into play within the area of age and language, such as the rate of language acquisition for the young and the rate of language attrition for the elderly. Specifically, this paper is seeking to define the variation between different age groups linguistically. We are going to divide these variations into three separate categories: language of a subgroup with membership associated with a certain age range, age-graded variation, and indications of linguistic change in progress.

First, the language of a subgroup associated with a certain age range is associated with social groups such as gangs, clubs, and other groups that involve the young. Typically, these groups are indicative of the environment where the youths find themselves. While the cultural norms may not be to speak in this manner, even in that environment, the group itself will create a sort of sub-language which the group’s members use respectively to indentify themselves as part of that group. There are a variety of reasons that they use different language from that of the cultural norm. It may be that they are trying to limit potential members by using language that is not expressed by the norm. It may be that they are seeking to antagonize or ostracize those who are not members of their group. Whatever the cause may be, the distinction is made within the group, not without.

Second, age-graded variation refers to a distinction that a generation should hold and use as it grows older but does not. An example of this is presented by author J. K. Chambers in his book “Sociolinguistic Theory”. He shares that in southern Ontario, Quebec the final letter of the alphabet (Z) is referred to as “Zed” which is the same as the French alphabet’s “Z”, however it has been Americanized by many to be pronounced “Zee”. The children were surveyed and two-thirds of them finished off the alphabet with “Zee”. The adults were also surveyed and only 8% of them finished off the alphabet with “Zee”. However when the same group of children and adults were interviewed later (the children were around twenty-five at the time of the second poll), the number who used “Zee” was much lower. He states, “Instead of marking a change in progress, the high frequency decreases as the generation grows older. It is therefore an example of an age-graded change” (p. 207). This is different from what normally happens which is that language normally follows a change in progress.

Indications of linguistics change in progress refer to the apparent-time hypothesis. This hypothesis states that differences in speech are often indicative of a change in progress. Basically it means that if individuals in their early 20’s, midlife individuals, and the elderly will all have linguistic qualities in their speech that indicate what has happened within the beginning of their generation or during their lifetime. In “Social factors in language change”, William Bright states, “Two fundamental facts of language are (a) that it is always changing, in all areas of structure (phonology, grammar, discourse style, semantics, and vocabulary) and (b) that it changes in different ways at diverse places and times” (81). In short, what he is trying to say is that what happens to a certain social group or culture at a particular time usually affects their language. For instance, the events that took place on September 11, 2001 have led to new terminology, denunciation of certain words, and accents being changed to avoid being stereotyped. We’ve looked at how age variations can affect language, now we are going to look at how geography distinguishes languages from one another.

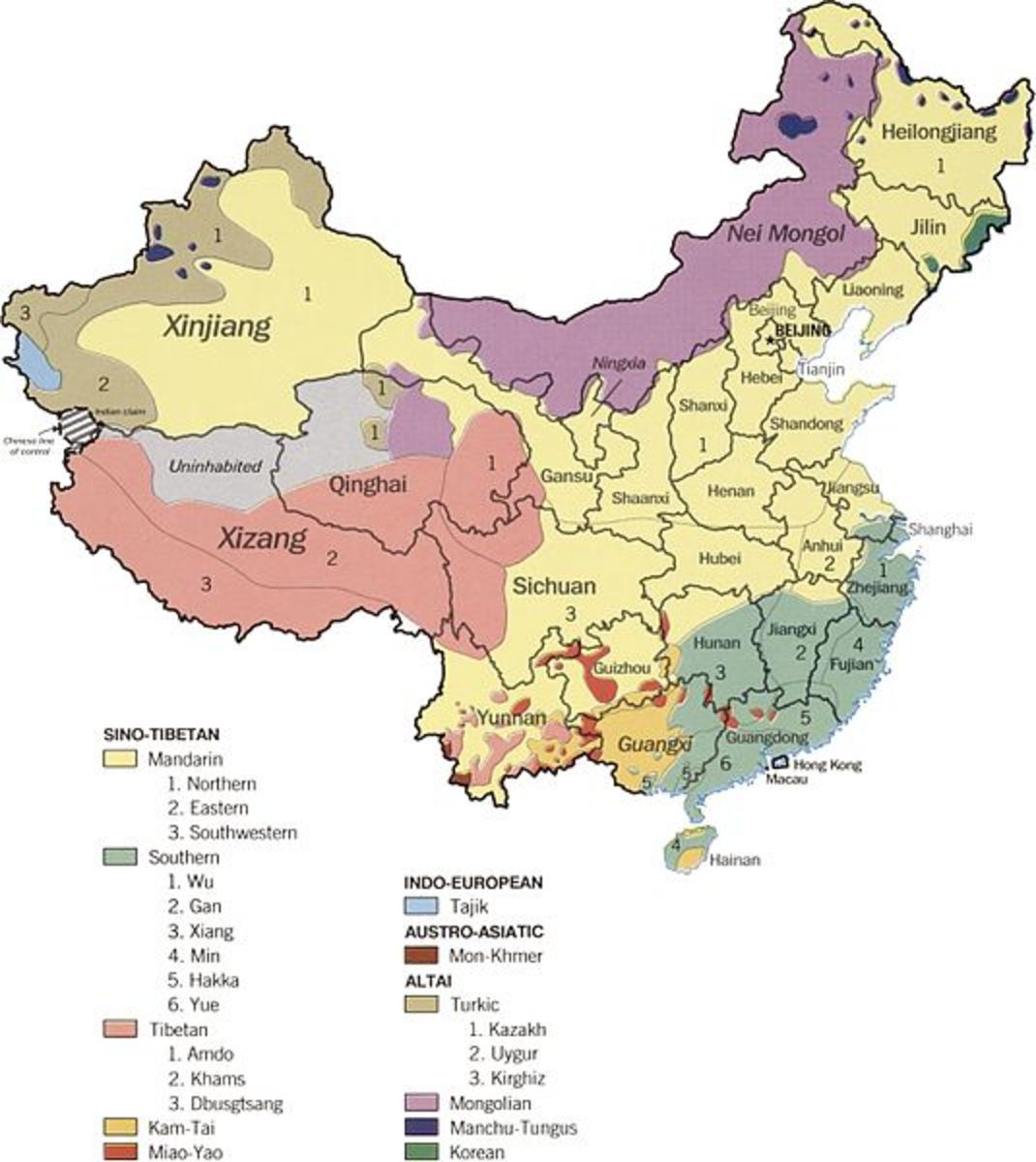

Differences according to geography

It is well known that in most countries, language is manipulated into different dialects based on the geographical location of a certain social group. These are called “regional dialects”. This too, is a broad topic; however we are only going to broadly cover the differences between regional dialects. The study of dialects is called dialectology. It is important to note here, that although many may criticize dialects as being improper English or other native language (which is an incorrect view); it is dialectology that opened up the field of sociolinguistics. That being said, dialectology is also important because it helps us understand why certain regional dialects are different from our own.

Regional dialects are said to follow certain geographical features such as mountains, rivers, etc. For instance, in certain places in the mountains of West Virginia there are extremely diverse dialects. This is due to separation from outside society. While they may understand each other’s words, an outsider may think that they are speaking gibberish. It is to be emphasized that this is a dialect, not a deviation from what is accepted. Therefore, America’s prestige dialect of SAE is not to be regarded as the actual language, but only the most common dialect of the English language. In their book “Dialectology”, J. K. Chambers and Peter Trudgill state that, “a language is a collection of mutually intelligible dialects” (p. 3). This means that all dialects should be treated as equal, just different.

With these distinctions of dialect came dialect maps. These maps are said to mark geographic lines which are divided by some geographic feature that divide different dialects. For instance the Rocky Mountains are a geographical feature which divides different dialects. William Labov, a prominent figure in dialectology, created a dialect atlas of the United States that marks phonetic distinctions between regions (regional dialects). This atlas was made by distributing various questionnaires and analyzing the data to see which phonetic features are homogenous to certain regions. Originally in one of his first articles, “The Three Dialects of English”, he decided that there were only three major dialects in the United States (p. 3). However, working with a group, he ended up dividing the map of the United States into four major dialect regions: (1) the Inland North, (2) the South, (3) the West, (4) and the Midland. The major dialect regions were then subdivided into sub-dialects.

According to the report by The Telsur Project of the Linguistics Laboratory of the University of Pennsylvania, William Labov, along with Sharon Ash and Charles Boberg, wrote that the Inland North is “defined by a revolutionary rotation of the English short vowels, which historically have remained stable since the 8th century.” The South is characterized by what they call, “the well known southern feature, the monophthongization of /ay/”. The West is characterized by “the merger of long and short open /o/.” And finally, The Midland is characterized by no single feature, but its cities each hold their own unique sub-dialect. For instance, Philadelphia holds a very different dialect than St. Louis does, however they are unique to the midland areas. Labov lists the key city dialects as: Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, Columbus, Cincinnati, Indianapolis, St. Louis, and Kansas City.

These distinctions are said to have emerged from how the nation was settled. First the north was settled, then the south. The west was developed from the northern dialects and the southern dialects moving westward along with the colonization. That is why the west doesn’t hold very specific individual dialects. And finally, during the civil war, the midlands became the dividing line between the north and the south, and eventually developed their own dialect. This led to the current major dialects that make up the language of American English.

In closing this section, it is important to mention that there is a move for dialect leveling. That is, there is a movement to make a single dialect out of the United States’ various dialects, and therefore establish a universal dialect for America. This movement has gained much criticism because many believe that it is labeling some dialects as less important than others. However, proponents of this idea state that it is not in criticism of any dialect, it is to ease into what is considered the most important aspect of any language, mutual communicability. They state that it will allow for better understanding and communication in general. Many would say that this is what has been attempted with SAE; however supporters are proposing incorporating all aspects of the various dialects into a universal dialect, not trying to make them all like SAE. As controversial as this topic has become, we are going to look at one final set of differences in sociolinguistics that has become even more controversial.

Differences according to gender

This area of social linguistics is the differentiation of language according to gender. This distinction is opposed by many groups, especially radical feministic groups that claim that there are no gender distinctions. As stated earlier, it impossible to say that any feature is unique to one certain group. That being said, these features are not unique to only one gender. I am merely noting frequency, based on previous research (someone else’s), of features that are more likely to be from either men or women. These features have been analyzed through a series of studies based on quantitative research.

A report by Deborah Tannen, titled “Women and Men in Conversation”, suggests that men have a “report” style, aiming to communicate factual information whereas women have “rapport” style, aiming at building and maintaining relationships (p. 211-213). This study as well as others suggests that these differences are easier to distinguish if one observes a group that is single-gendered. This is because if they are focused on communicating with members of the same sex they will communicate in that manner, however if both sexes are present it may result in multiple communication styles in order to communicate in both ways.

One certain noticeable difference between genders in communication that has been listed is how each sex responds with minimal responses. For instance, it has been noted that women use placeholder features such as umm, hmm, and yeah to encourage communication. They are not necessarily there to agree or disagree with the conversation, rather just to facilitate conversation. For men, these features are to agree or disagree with the information that is presented to them, usually only the latter.

Another difference is in the usage of questions. Whereas men use questions to obtain information, women may use questions rhetorically. Even though a woman may already know the answer to the question she is asking, it is used to facilitate conversation or to encourage verbal engagement. Men are seeking only to find out what they want to know and no more.

While I could go on for quite a while with other distinctions I am going to just name several without fully elaborating on all of them. Some distinctions are the way in which men and women: listen, take turns in conversation, take control of the conversation, change the topic of conversation, have degrees of respectfulness, disclose information, address another individual (“verbal aggression”), etc. These distinctions are helpful to know because they identify better ways to converse with members of the opposite sex, as well as members of their own gender. In a study by William Labov, labeled “The Intersection of Sex and Social Class in the Course of Linguistic Change”, he points out that although these distinctions do exist and can be identified, it common for there to be what he refers to as “the reversal of roles” (p. 8). This is where a man uses linguistic qualities that a woman would normally use in conversation and vise-versa.

Conclusion

We’ve looked at differences according to social class, differences according to age variation, differences according to geography, and differences according to gender, but why is it important to notice these differentiations? Well, there are a variety of reasons why this is so important. For instance, these differences distinguish one human being from another. It is what make us unique but still similar. It is the universal language of diversity. It is important to recognize in a world of diversity in language, we are a product of the words that we use, which is to say we are in some way diverse ourselves. These social language features that distinguish one from another identify us with a particular class, age, area, or gender; however it is important to know that we all ingest language individually. We each have our own dialect of sorts. However it is also important to state that this “idiolect”, as it is named, is still a product of the environment where we were raised or it is in opposition to the environment where we grew up. Either way, in some way sociolinguistics plays a vital role in our understanding of our language, which plays a vital role in understanding ourselves.

Bibliography

Bernstein, Basil (1964) Elaborated and Restricted Codes: Their Social Origins and Some Consequences, American Anthropologist, Vol. 66, No. 6, Part 2: The Ethnography of Communication, Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

Bright, William (1997). "Social Factors in Language Change", Coulmas, Florian (ed.) The Handbook of Sociolinguistics. Oxford: Blackwell.

Chambers, J.K. (1995). Sociolinguistic Theory, Oxford: Blackwell.

Labov, William. (1990). The Intersection of Sex and Social Class in the Course of Linguistic Change. In Ed. 2 Gender and Discourse. New York: Oxford University Press Inc.

Labov, William. (1991). The three dialects of English. In P. Eckert (ed.), New Ways of Analyzing Sound Change. New York: Academic Press. Pp. 1-44.

Labov, William (1996). The organization of dialect diversity. Paper given at ICSLP4, Philadelphia, November 1996. Phonological Atlas of North America, http:/www.ling.upenn.edu/phono_atlas/home.html

Tannen, Deborah. (1991). You Just Don’t Understand: Women and Men in Conversation. London: Virago.

Wardhaugh, Ronald (2006), An Introduction to Sociolinguistics, New York: Wiley-Blackwell